Katago - a Japanese folktale retelling -

Once upon a time, there was a hard-working young farmer named Suekichi.

Despite all his efforts, the times were hard, landlords were harder and

so he was very poor. But there was one thing in his life that gave him

joy, Fuku, his lovely wife. Her beauty was famous in several villages

and many youths had vied for her hand. Suekichi could hardly believe

his good fortune when she fell in love with him, a poor farmer with few

prospects.

Perhaps it was on account of his crooked nose. For Suekichi had a most

unusual nose. No, he hadn't broken it falling out of a tree or in a

fight, for our Suekichi was a pacifist. His father and his father's

father had had crooked noses so apparently it was in his DNA. In any

case, there it was, a most crooked nose. But Fuku had found it to her

liking.

Even now, Fuku shone like a bright pearl dancing in the sun as she

stooped again and again in a steady rhythm, planting young green shoots

in the rice paddies.

But someone else's eye had been caught by the glowingly fair sight. A

strangled gasp and she was gone. Kidnapped by a terrifying Oni from the

far reaches of the globe. Suekichi ran after them with all his strength

but had no hope of catching them, for the Oni was riding a magic cart

that could fly a thousand miles with every bound. And certainly not

even the fastest Olympic sprinter could match that pace.

Gasping with fury and hypoxia, Suekichi finally collapsed on the packed

dirt road and sobbed his eyes out.

A few hours later Suekichi was on his way. He was going to bring to

Fuku back, no matter how long it took.

Ten years later, he was still searching.

And finally, it seemed he really had arrived at the far reaches of the

globe.

He'd first made a visit to the deep mountains of Mie where it was said

a famous sennin (holy person) lived. No one knew whether the sennin was

a human or a Tengu (the playful spirits with impossibly long noses),

but Suekichi had made offerings of sake and rice cakes and begged for

advice on how to reach the land of the Oni. He'd gotten his answer

several days later, a single pure white crow's feather, pointing north,

north-west.

Suekichi could now make out an island in the distance, wrapped in a

thick dark fog. He'd spent several days building a raft and stepped

aboard for the final leg of his journey. Tossed by wild waves, Suekichi

was in danger of falling overboard many times but finally, finally, he

reached the land of the Oni.

As he slowly crept ashore, the first thing to catch his attention was

some chanting in children's voices. Wondering what children were doing

in a place like this, he peeked out from some shrubs and saw a group of

Oni children in a circle, poking sticks at something in the middle. A

turtle? Oops, wrong story. No, it was another child. But one with

pearly skin, just like... Suekichi didn't want to believe his eyes. But

the child was just the right age, maybe eight or younger. And obviously

not all Oni.

Suekichi's knee-jerk reaction was to do an about-face and head straight

back to his neglected rice paddies. There was obviously nothing for him

here anymore. But just then, the halfling child looked up. In his

tear-filled eyes, Suekichi saw the woman he had longed for so long. And

besides, Suekichi was hardly one who could ignore the pain he could see

reflected there.

Although lacking pointy ears and hairy feet, Suekichi was quite a hand

when it came to throwing stones, and had often managed to supplement

his vegetarian diet with a sharp eye and good arm. He hunted around for

likely stones and then found a strategically-placed tree with rich

foliage to hide in. Then one by one, he picked off the pickers-on. They

ran off in all directions, crying. Finally, only the little boy in the

middle was left.

Suekichi scampered down the tree and made his way over to where the

child huddled in fear and sorrow.

"Um... Hi, there." Suekichi said awkwardly. The boy seemed ready to

scream but somehow managed not to.

"Can you take me to you mother? I mean, if she's alone... I don't think

I want to meet your dad."

The boy nodded and started walking.

The boy carefully took the back streets, leading Suekichi to a huge

house in the middle of the village. They sneaked through the back

entrance, through some long dark hallways to reach a room which glowed

from the sheer luminescence of the person within. It was Fuku.

Although she was now dressed in rich Oni garb, there was no mistaking

her. She was thinner and there was a tremendously sad look in her eyes

which brightened slightly at the sight of her son, but it was

definitely Fuku. Suekichi quietly slipped out of the shadows where he

had been hiding and Fuku's eyes widened. For a moment, the sadness

disappeared but then returned, deeper and darker than before.

"Suekichi" she whispered. Ragged, long-haired and bearded as he now

was, there was no mistaking that nose.

"We're going home Fuku. And we're taking our son"

The sadness broke and was transformed into a flood of tears which Fuku

just barely managed to keep at bay as she whispered,

"Wait. Give me a moment to get ready", and rushed off to the treasure

room. Suekichi followed and found her loading treasures into one of the

magical carts. "Hurry. You load the other one. We'll have to take them

both or he'll catch up to us in no time. This one travels two thousand

miles in a bound while the other travels one thousand per bound. If we

take them both, he won't be able to find us for some time."

Within ten minutes, they were ready to leave. But it was one minute too

late, for the boy's father was now stamping his way down the corridor

yelling, "Fuku! Where are you?"

Fuku scrambled into one of the carts and quickly explained how to drive

them. Amidst the noise, Suekichi couldn't quite catch what she told

him. The Oni stamped into the treasure room and spotting Suekichi, had

already grabbed his deadly iron-studded club. Just as the Oni swung his

club down, the little boy jumped in front of Suekichi and took the

blow. The boy mumbled the words to start the cart and they were off.

Fuku followed immediately after, the Oni's moans of anger and grief

still ringing in her ears.

In a few minutes, Suekichi and the boy had arrived home. And several

minutes later, for she had taken the slower cart, Fuku arrived.

Suekichi had laid the boy out on a futon and was trying to make him as

comfortable as he could. It did not seem likely the boy would survive.

Fuku rushed to his side and grasped his hand. With the last of his

strength he whispered,

"Mother, it's better this way. I wouldn't have been happy here either.

Do something for me, please. When I'm dead, cut off my head, put it on

a stick and set it up outside your house. You know my father is coming

after us. If he sees my head, it should scare him off. And if

that doesn't, remember, his eyes are his weakest point..."

A single tear flowed down his cheek as he drew his last breath.

Fuku sat there, head bowed and still holding his hand. But in less than

five minutes she stood up with a determined look on her face.

"We can't let his sacrifice go to waste. And we haven't much time."

Suekichi, still shaken himself, put his hand on Fuku's shoulder.

"No. We can't. We shouldn't. But I have an idea."

Suekichi rushed to a neighbor's house and made a very strange request.

Shaking his head, the neighbor complied, while the neighbor's cat gave

Suekichi a dirty look.

In the meantime, Fuku had hidden away the two carts and was trying to

fortify the area around their house. Suekichi brought two long sticks

and stuck his neighbor's gift on them. They were sardine heads, quite

whiff from having been allowed to ripen for some time. Suekichi quickly

threaded some holly leaves through the sticks to add to the warding

effect. And then he stuck the sticks up in front of the house.

Fuku wrinkled her nose. "Actually, I think those smell even worse than

my son did. The smell alone should scare his father away."

"Fuku! I'm surprised at you."

"Stinky odor is a compliment among the Oni. Why do you think I wear

these?"

Fuku held one nostril closed as she snorted heavily and then did the

same for the other nostril.

Out popped two soybeans as Suekichi watched horrified.

They fell into the ground, sprouted, then began to grow at an

unbelievable rate. Before their very eyes, the soybean plants had

spread out and were soon heavy with bean pods.

"Oh, I forgot. Those were magic Oni soybeans. They're as hard as

pellets and don't taste good at all" sighed Fuku.

Suekichi looked at them with a strange glint in his eyes.

"Ammunition!" he suddenly announced, "Fuku, help me pick these. Right

away!"

Fuku only looked confused for a moment. Then, she was stooping to

quickly gather beans left and right.

The Oni didn't come that night.

Or the next.

But just as the sun was starting to set on February 3rd, the ground

began to tremble.

"Oh, oh. That's him. He does that when he's upset", Fuku remarked as

they rushed into the house.

Quickly the two grabbed the beans which were now harder than ever now

that they'd had time to dry out a bit.

The Oni had arrived on their doorstep. Admittedly, the fish heads had

given him pause. He'd reeled away staggering and waving his hand in

front of his face. Now that several days had passed, they were riper

than ever and even the local cats were giving them a wide berth.

But the Oni was determined to take his revenge. He went back several

paces to where the air wasn't quite so toxic, took a deep breath and

held it. Then waving his deadly club he rushed in to attack.

"Aim for the eyes. It's his weakest spot", Fuku reminded.

Yelling, "Out with the Oni, in with Fuku! Out with the Oni, in with

Fuku", the couple threw handfuls of soybeans at the Oni. Obviously,

quite a few must have found their mark. And of course, the Oni probably

got a nice good gulp of sardine-tinged fumes when he yelled out in

surprise. Before long, he was on his way home, screaming with pain and

fear.

* * *

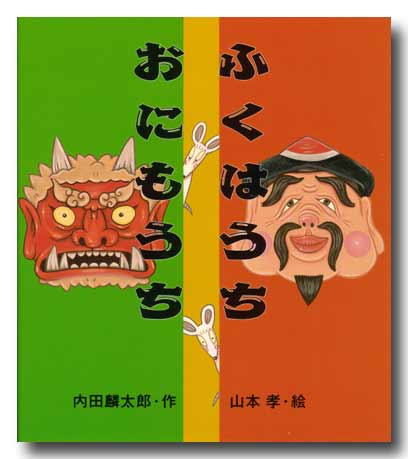

In almost every culture, there are festivals to celebrate the end of

winter and the coming of spring. This is one of the Japanese versions.

On February 3rd, a day we refer to as "Sekku" or changing of the

seasons, most Japanese families engage in throwing soybeans at the Oni

(usually the father of the household wearing an Oni mask) yelling, "Out

with the Oni, In with Fuku". "Fuku" means "Good Fortune" so this is a

wish for good fortune to come into the home and for all evil,

represented by the Oni, to leave. Like birthday candles, family members

must each eat the same number of soybeans as years they've lived, with

one extra for good luck. This is believed to lead to good fortune and

health for the coming year.

This particular retelling is one that

I've compiled from several katago stories I've read in the past and

adapted

for a western audience. By no means is it meant to be the

definitive pourquoi tale to explain why we throw soybeans so be sure to

watch for other versions as well.

There are also other traditions associated with this holiday. One

involves the eating of uncut sushi rolls facing a specified direction

of good fortune for that particular year. The sushi rolls are left

uncut because we hope to retain our "ties" to friends and good fortune

uncut. Another tradition is to eat sardines on this day. Not only is it

a good source for the fish heads, but often, the fish is cooked on a

barbecue placed right outside the front door and the fishy smell is

supposed to scare the Oni away.

(Sako Ikegami)

|

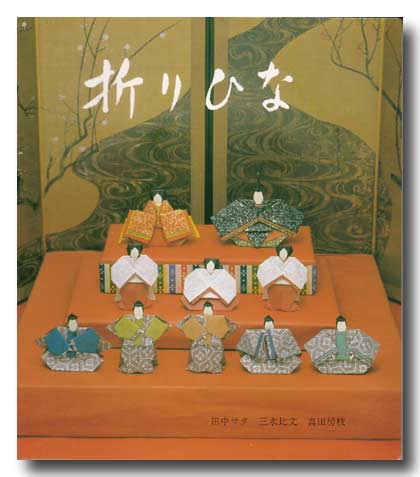

A Picture Book for

Spring

A Picture Book for

Spring